Update, March 18: County health officials report the Taqueria Las Torres food truck passed its re-inspection today and received approval to reopen after operators worked with officials to address previously identified food safety risks.

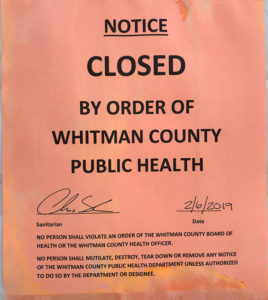

County health officials took the uncommon step of ordering the immediate closure of the Taqueria Las Torres food truck in Pullman earlier this month after inspectors observed food prep in the adjacent dilapidated rail car.

Public Health Director Troy Henderson said the department tries to work with restaurant owners to keep doors open while they address inspection deficiencies, but the taco truck operators did not comply with a previous warning about their food handling practices.

“There are safety standards you just have to make,” he said. “We only close a place down every few years, so it’s quite rare.”

The county’s Environmental Health program inspects approximately 150 establishments on an annual basis. Records show six local restaurants failed inspections in 2018, five failed in 2017 and just one failed in 2016. See a complete log of the inspections, scores and failure reports below.

Records show insufficient hand-washing practices, improper temperature controls and poor food storage make up the most common issues.

Henderson said an immediate closure reflects imminent health hazards. The Feb. 6 inspection report cites food prep inside the nearby caboose. Raw food surfaces were not cleaned properly. Dishes had filled up the hand-washing sink. Employees stored de-icer chemicals above food.

“Public safety is the No. 1 priority,” he said.

Officials noted they had sent the owners a compliance plan to work toward re-opening, but had not received a response. Whitman County Watch left a voice mail at a number listed for the establishment without reply.

Environmental Health Director Chris Skidmore said restaurant inspectors schedule checks on a “risk-based frequency,” so a simple coffee stand may get inspected less regularly than a full restaurant. Inspectors also try to visit during peak serving hours based on the type of restaurant.

“We just show up with a clipboard,” he said, noting they do not warn owners.

Inspectors use a standardized form that tallies red points for high risk deficiencies and blue points for low risk practices. An establishment fails its inspection if it gets cited for more than 40 red points or more than 50 combined points. Those restaurants must pay $150 for a re-inspection.

“We’ve been more than willing to work with restaurants … to get them back in compliance,” Skidmore said. “We’re not here to shut them down.”

The department also handles inspections for kitchens at local schools and some WSU Greek houses. Its enforcement procedure outlines the steps for getting re-inspected or renewing permits.

Chelsea Cannard, one of three county inspectors, said local data shows the most common sanitation issues involve inappropriate hand-washing practices as well as inconsistent food temperature controls. Department staff prioritize bacterial and contamination risks.

“Those are the main things I try to look at,” she said. “I try to take a process approach: What are they doing? What should they be doing?”

Most of the restaurants that failed in 2018 had problems with washing stations or failing to wash hands between tasks. Inspectors did not observe any hand washing during an August visit to Cougar Country Drive-In and Tokyo Seoul did not have any towels at its washing station.

Some establishments also struggle with food storage, stacking raw meat in areas above ready-to-eat food, or improper thawing procedures. Inspectors often notice risks from cross contamination when food gets moved across cutting boards or other prep surfaces without regular cleaning.

Henderson said one of the more consistent predictors of inspection failure depends on whether a restaurant is locally-owned or part of a national chain. Corporate chains often enforce more rigorous health practices.

“They have standards which they have developed over decades and thousands of locations,” he said, adding that corporate entities may inspect local franchises several times a year.

Skidmore noted the complexity of the restaurant’s menu can also expose food prep operations to higher risks of deficiency. Making lots of different cuisines with multiple prep and reheating stages in a tight space results in greater potential for cross contamination or other issues.

“It doesn’t matter how skilled they are,” he said. “If they’re trying to do tons of stuff in a small kitchen, … it’s just easier to find stuff. (And) a lot of Asian restaurants have very complex menus.”

Inspectors emphasized they try to build positive professional relationships with local operators to establish mutual understanding and respect. They find better compliance with owners who embrace the importance of food safety and take the process seriously.

“We all go in with the approach that we’re here to help you do what you do in a safe way,” Henderson said. “You understand their role. They understand your role. You want them to be successful.”

Officials noted the inspectors only observe a small window of time, but Henderson said he has previously worked in areas without regular food inspections and has seen how safety standards suffer.

“Over time, if there’s not somebody coming in and keeping them on the right path there is drift toward what’s a faster way, what’s a more economical way,” he said. “(But) if you’re out there doing your job regularly and professionally, it’s easier to maintain.”

Environmental Health also conducts air and water quality testing, water recreation facility certification, septic site approval, solid waste inspections and other programs. The department reports to the county Board of Health.

After Whitman County Watch requested the county’s annual inspection scores, the department has since posted those publicly here.