Whitman County officials rejected about 250 questionable ballots in the 2020 General Election, a percentage on par with other recent elections, mostly based on signature problems or seemingly impatient voters trying to resubmit their ballots.

County Auditor Sandy Jamison said an emotional presidential race and the COVID-19 pandemic made for a wide variety of potential challenges, but staff preparation and community cooperation paid off. Officials invested in new ballot drop boxes, security guards and a student voting center at WSU.

“We all know how polarized this election was,” Jamison said this week. “We put in an awful lot of preplanning. It went much smoother than it could have.”

Washington state awarded its Electoral College votes Monday after local officials had certified county ballots back on Nov. 24. Whitman County counted a total of 21,293 ballots this year for a turnout of just over 86 percent. Voters returned nearly 3,000 more ballots than in the 2016 election (18,328 ballots).

The three-person Whitman County Canvassing Board, which included Jamison, County Prosecutor Denis Tracy and County Commissioner Michael Largent, reviewed approximately 650 questionable ballots in a public meeting on Nov. 23. Read the final reconciliation report here.

Many problematic ballots get “cured” when election staff contact the voter to confirm their signature or other information. On remaining ballots, the board compares signatures, postmarks and other factors in an effort to verify the validity of each ballot. Jamison said each ballots gets its own consideration and discussion before being accepted for tabulation or rejected.

Read our previous coverage about how the Canvas Board process worked in 2019 (172 ballots rejected) and in 2018 (nearly 300 ballots rejected).

About 1.2 percent of returned ballots were rejected in Whitman County this year for various problems compared to 1.6 percent last year and 1.4 percent in the 2016 presidential election. Historically, the county does tend to rank high in the percentage of ballots it rejects compared to other counties in the state.

The local board ultimately rejected 139 ballots with questionable signatures, 10 ballots with missing signatures and 15 ballots with late postmarks. Another 84 ballots were rejected for miscellaneous reasons. One other rejected ballot made 249 total.

Jamison said the board saw a higher number of resubmitted ballots this year as some antsy voters tried to resend a second ballot after failing to see the first one show up as received in the online voter system. Jamison noted the prosecutor was on hand for those discussions and found no evidence of criminal intent. Officials only counted the first ballot received.

“We found no fraud in that,” she said. “That was basically impatient voters. … They just wanted to make sure we got at least one of their ballots.”

Jamison acknowledged increased tensions around this election as national anger and anxieties trickled down to local races. She wrote a letter to the Whitman County Gazette last week disputing a local Republican election observer’s complaints of fraud and insufficient observer access.

“We have had voters that are frustrated with the entire system,” Jamison said. “We’re as transparent, I believe, as we can be.”

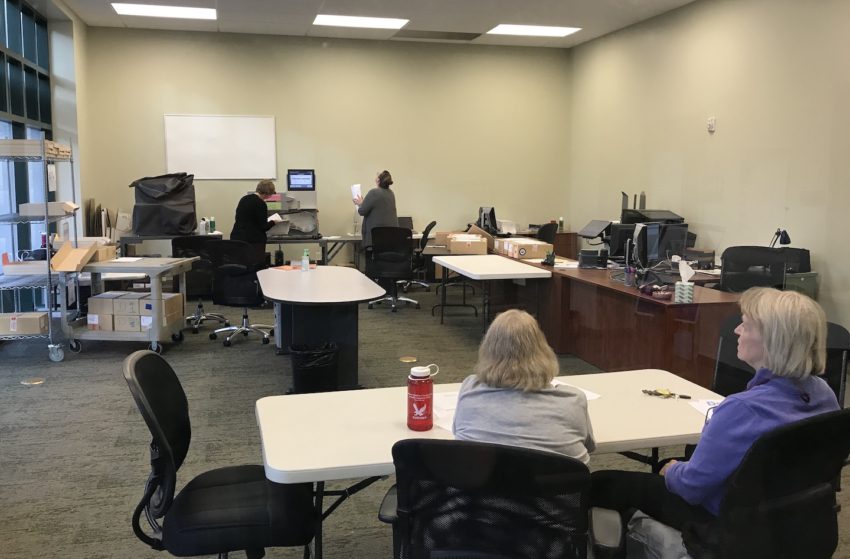

Due to COVID-19 social distancing protocols, election observers watched this year’s count from behind a large window that separates the ballot processing room from the front entry way. Observers typically sit just inside the window, only a few feet closer to the sorting and tabulation stations.

Jamison, who ran as a Republican, said she discussed the ballot verification and counting process with several observers throughout the multi-day tabulation and answered any questions as best as she could.

After discussing potential concerns with other county auditors, Jamison said she also brought in security guards to the Elections Center to help keep the facility secure and welcoming throughout the vote. She did not report any disruptions.

“I was really just trying to be proactive,” she said. “I wanted the voters to feel comfortable. … I knew we would potentially have emotional people.”

Jamison also invested in three new ballot drop boxes in Pullman this year in anticipation of high voter turnout. She estimated three times as many local voters returned their ballots to drop boxes instead of by mail amid national controversy over U.S. Postal Service slowdowns.

Election staff made rounds to collect ballots from the boxes daily, which Jamison said they have never had to do before: “They were full.”

A recent court ruling has ordered the state to pay county governments to install additional ballot drop boxes. Jamison said she has not yet extended her plans for new boxes as the decision goes to appeal.

A voting center at WSU also saw nearly 500 people on Election Day as students and others registered to vote and returned their ballots. Jamison said she was impressed with the turnout as well as the university’s sanitation efforts. (She noted none of her staff reported COVID-19 symptoms in the wake of the election.)

Despite the many new challenges, the November election also avoided the kind of ballot mixups and omissions that have plagued other county races in recent years.